An escape behind enemy lines – The story of Pte. Peter Cormack

This post is also available in:

Nederlands

Nederlands

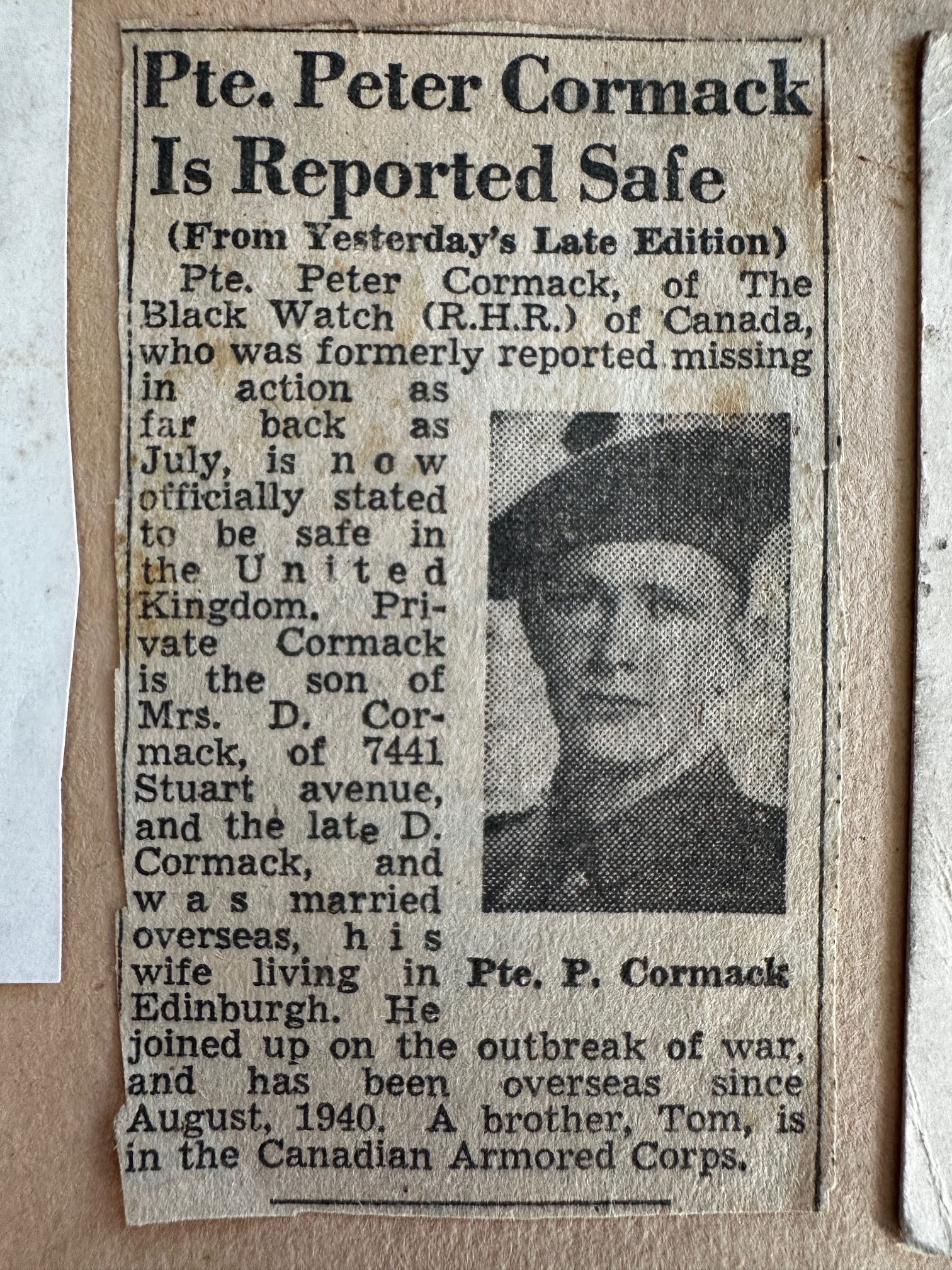

Some time ago, I purchased a remarkable set of documents belonging to Private Peter Cormack (D81507) of the 1st Battalion, Black Watch of Canada. On July 27, 1944, following the bloody assault on Verrières Ridge, Cormack was taken prisoner in St. André along with a medical orderly.

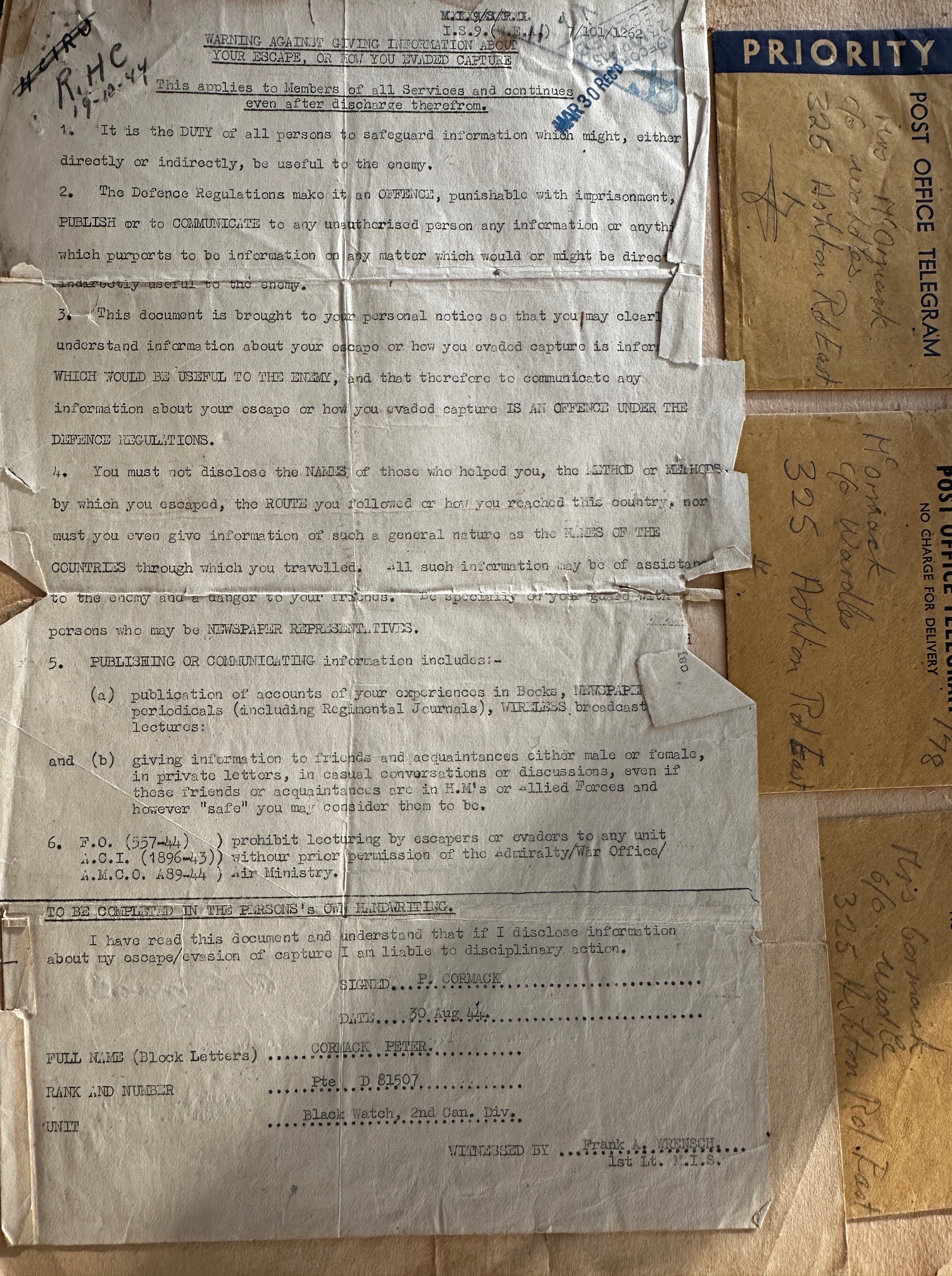

While being transported to Germany, he managed to jump from a moving train on August 8, along with nine others. After weeks on the run and hiding with the help of the French population, he reached the advancing American forces near Coulmier on August 27.

Operation Spring: The Canadian Battle for Verrières Ridge

Since the landing on D-Day, June 6, 1944, American, British, and Canadian troops had been engaged in a grueling battle with the Germans in the notorious Normandy bocage landscape. Every inch of ground was fought for with blood, sweat, and sacrifice. In this chaotic terrain, full of hedgerows and narrow roads, the German army managed to regroup in early July 1944 and effectively encircle the Allied bridgeheads. This resulted in a stalemate reminiscent of the trench warfare of World War I. While the Red Army rapidly advanced through Eastern Europe, crushing German divisions, the Western Allies seemed to be bogged down in Normandy. Political pressure in London and Washington—partly due to the upcoming U.S. presidential elections—intensified. The call for a breakthrough grew louder. Under this pressure, General Eisenhower ordered a large-scale offensive, with Operation Cobra on the American side and Operation Goodwood—with its Canadian component Operation Atlantic—on the British side.Goodwood started promisingly on July 18, 1944, but stalled two days later against the heavily defended terrain of Verrières-Bourguebus, south of Caen. The Allies suffered heavy losses and lost their momentum. Yet, there was one bright spot: on the west side of Verrières Ridge, a small gap seemed to be opening in the German lines. Although initially not exploited successfully, this gap became the impetus for a new Canadian attack: Operation Spring.

The ambition of Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds

Operation Spring was conceived by Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds, commander of the 2nd Canadian Corps. Simonds, whom Montgomery described as “the best of a mediocre bunch,” hoped to force the long-awaited breakthrough through this operation. His plan was to capture the Verrières Ridge by night and thereby flank the German 1st SS Panzer Division (Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler), which was entrenched in the eastern sector. Subsequently, German armored reserves would be drawn to the front, where they would come under fire from Allied tanks, anti-tank guns, and the air force. The concept initially seemed logical—similar to Montgomery’s earlier battles in North Africa—but the execution was marked by overcomplexity and rigid timetables. Simonds’ authoritarian leadership style and tendency to micromanage ultimately doomed the operation.

Canadian soldier R. Pankaski awaits the end of a medium-intensity artillery bombardment during Operation SPRING near Ifs on July 25, 1944.© Library and Archives Canada

A Canadian bloodbath

On July 25, 1944, Operation Spring began simultaneously with the American offensive near St. Lô. The Canadian attack soon stalled under intense German fire. Within a few hours, the two leading divisions of the 2nd Canadian Corps suffered 1,500 casualties, including 500 killed. The heaviest blow fell on The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada. In the afternoon, under the command of Major Griffin, they were ordered to continue the assault. The companies reached the ridge overlooking the town but were met with deadly concentrated fire. Nearly all the frontline units were wiped out; of the 320 men deployed, 300 were killed—a loss of 94% in less than four hours. Elsewhere, things also went wrong. The attack by Le Régiment de Maisonneuve on May-sur-Orne, intended to relieve pressure on The Black Watch, was likewise halted by intense machine gun fire.

In the chaos around The Black Watch, Sergeant James was killed by a mortar strike; Captain Stuart and many others were wounded. Ultimately, the remaining elements of The Black Watch were withdrawn at night to regroup. Only a few of the missing managed to return to the Allied lines—most of them wounded. As a result, July 25 became the day with the highest number of Canadian fatalities since the Battle of Dieppe in 1942.

Telegram to Mary Cormick informing her that her husband, Peter Cormick, has been missing since July 30, 1944. © Collection Joël Stoppels

In search of missing or wounded

The 27-year-old Canadian soldier Peter Cormack from Montreal was ordered on the morning of July 27, 1944, to go to Saint-André-sur-Orne to pick up wounded or missing comrades from his battalion after the fierce fighting for Verrières Ridge. Accompanying him were Lieutenant Geoffrey Somerset Cooke (from his unit) and the soldier Pickup, a medical orderly. Cormack was driving a 15-cwt truck. They entered St. André and turned toward a farmyard. Along the way, Cormack noticed that they might have gone too far into the village, as he saw no Allied troops nearby.

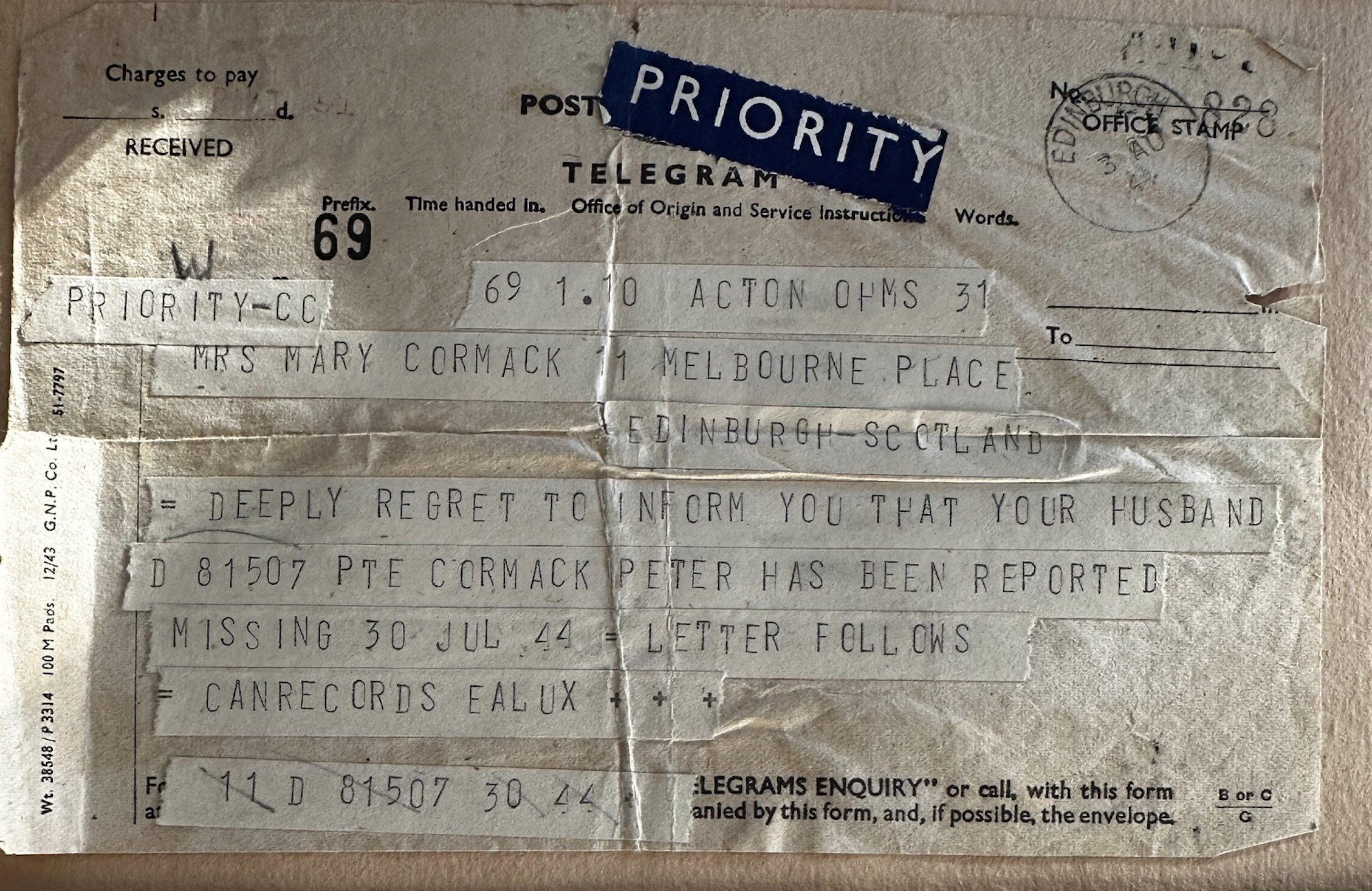

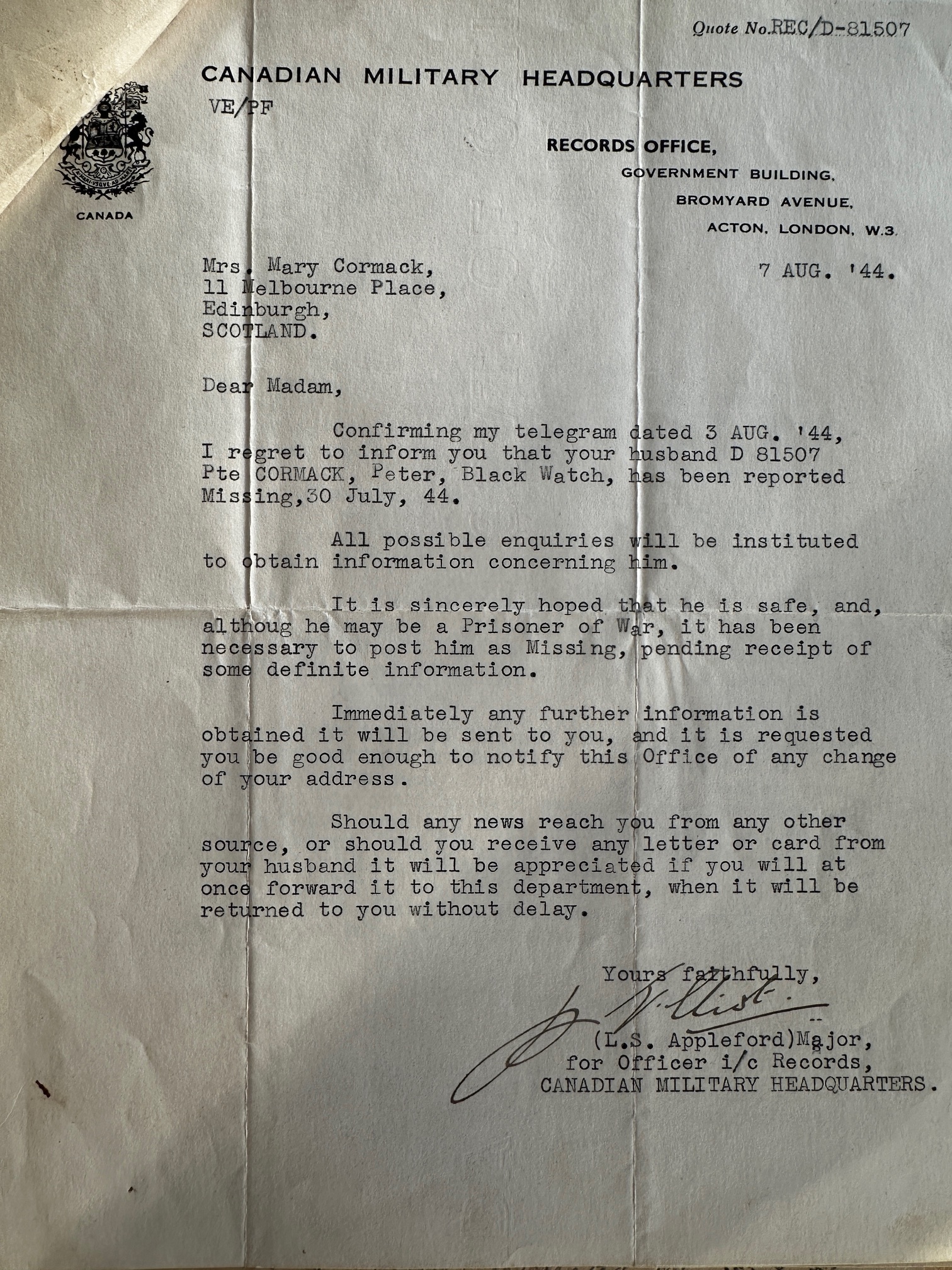

Lieutenant Cook replied that everything was fine. After they had parked the truck and walked onto the farmyard, Cormack saw a German inside a building. Lieutenant Cook opened fire with a Bren gun. This immediately provoked a reaction: four German machine guns opened fire, and the group was surrounded. Lieutenant Cook was fatally wounded; Cormack and Pickup were taken prisoner. At the same moment, a jeep entered the village carrying four soldiers from the Régiment de Maisonneuve; they were also captured. The group was then taken to a point about eight miles behind the front line. From there, they were transported by truck to a prisoner-of-war collection point holding around 200 men. Cormack stayed there for five days, until August 1. The food was very poor. Meanwhile, his mother received a telegram stating he had been missing since July 30, 1944. On August 1, he was transferred to a larger camp inland, housing about a thousand prisoners of war. He stayed there until August 4, after which he was moved for one day to a large camp near Chartres.

A letter to Peter Cormick’s wife informing her that he has been missing since July 30, 1944. © Collection Joël Stoppels

The escape from a moving train

On August 5, the prisoners were loaded onto a train bound for Germany. On August 6, they were given water, but for the following two days they received nothing. The situation was desperate: the air inside the wagon was poor, as 50 men were crammed into a single freight car. On the night of August 8, they broke open two small windows. Ten men, including Cormack, managed to escape during the journey, each at a different point. Together with an American, Tex Grant, Cormack headed southwest for about ten miles and they slept that night in a haystack. The next morning (August 9), they met two other escapees: soldier Gibson (from Cormack’s unit) and Sergeant Carol White of the U.S. Air Force. A farmer then directed them to a boy who took them to a farm about four miles away, where they could hide. There, they were given civilian clothes and their uniforms were confiscated.

Telegram to Mary Cormick informing her that her husband, Peter Cormick, is safely back in England. © Collection Joël Stoppels

They stayed at that farm, close to the main road from Paris to Château-Thierry, for two weeks. On August 21, the farm was raided by the Germans; the Maquis were also staying there, as it was a gathering place for the resistance. Cormack and Gibson fled into the woods, where they met an Algerian. Tex Grant stayed behind; Cormack does not know what happened to him or the others. Cormack, the Algerian, and Gibson continued on until they reached a farm near La Ferté-Gaucher, where they were able to eat and spend the night. The next morning (August 22), they moved on but got separated from Gibson. Cormack did not see him again until they met in London.

He and the Algerian traveled for two days through the countryside until they found a farm near Coulmier where they were allowed to stay for two days. They moved on afterward, as they did not feel safe there. On August 26, they made contact with a resistance group, which offered them shelter. They were questioned by the group’s leader, who turned out to be English. That night, the area came under fire from the American Third Army, and they had to take cover. On August 27, 1944, American forces entered the area. Cormack and Carol White managed to get a ride on American trucks back to Chartres, and from there Cormack was transported to Bayeux. There, he reported to a British major. Eventually, his mother received another telegram—this time informing her that he had safely arrived in England.

Sources:

– War Diary Black Watch of Canada, July 1944.

– Seven Days in Hell: Canada’s Battle for Normandy and the Rise of the Black Watch Snipers by David O’Keefe.

– The National Archives, Recommendation for Award for Cormack, Peter. 68/Gen/6896