The photo that never arrived…

This post is also available in:

Nederlands

Nederlands

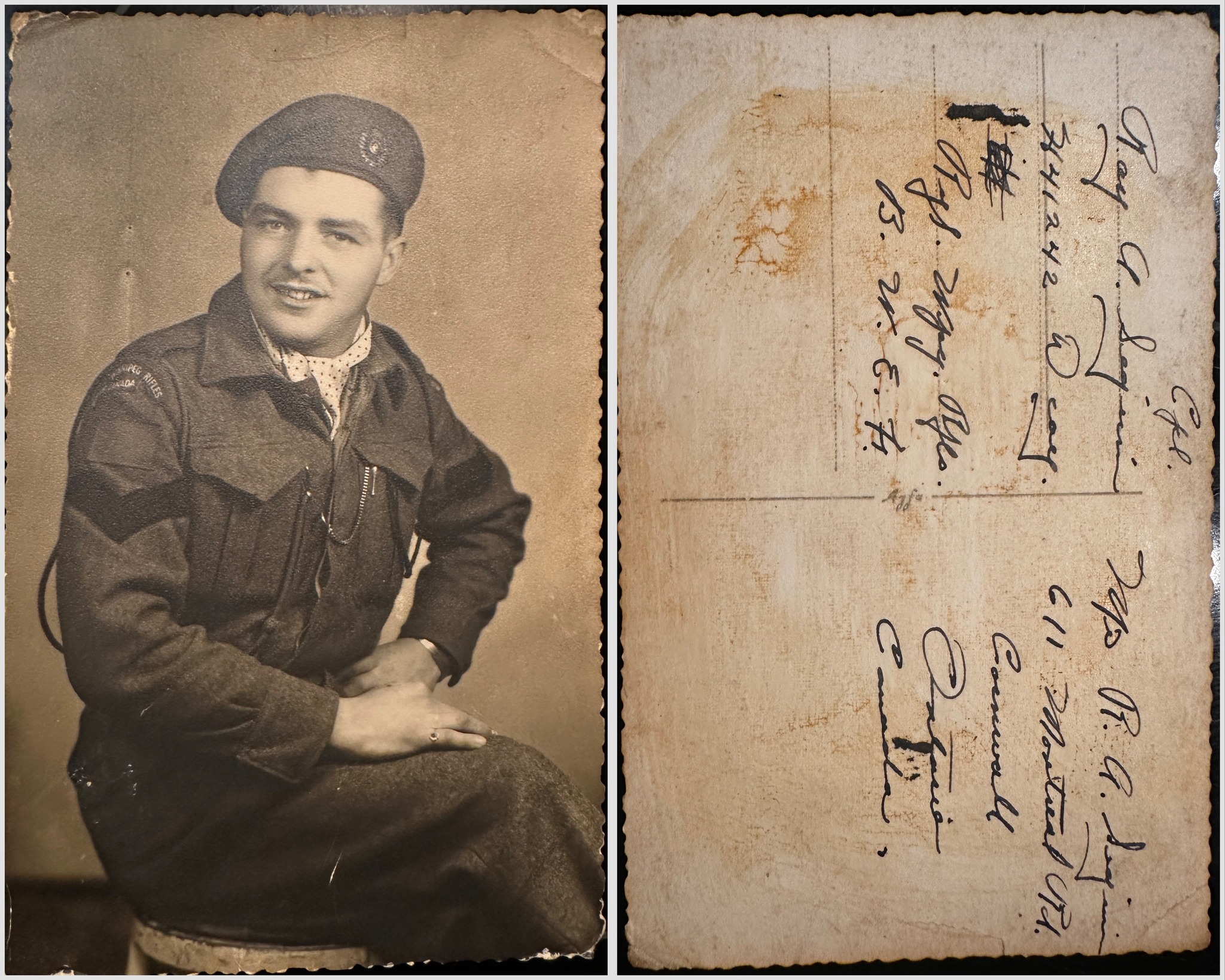

I bought an old black-and-white photo through Marktplaats. At first glance, it seemed like a random portrait of a Canadian soldier from the Second World War. A young face, posing rigidly in battledress, beret on his head.

But when I turned the photo over, I read the following:

Cpl. R.A. Seguin, H/41242, D Coy, Royal Winnipeg Rifles, B.W.E.F. – Mr. R.G. Seguin, 611 Montreal Rd., Cornwall, Ontario, Canada. What began as a chance purchase turned out to be the start of an impressive quest. Behind this portrait lay the story of Corporal Raymond Aureal Seguin, a young Canadian who would never send his photo home.

Raymond Aureal Seguin

What began as a chance purchase turned out to be the beginning of a remarkable search. Behind this portrait lay the story of Corporal Raymond Aureal Seguin, a young Canadian who would never send his photo home. Raymond Aureal Seguin was born on October 17, 1921, in Alfred, Ontario. He was the third of six children in a French-Canadian family. His father, Honore Seguin, passed away in 1935, leaving his mother, Blanche Clément, to raise the family on her own. Raymond grew up in impoverished circumstances but was known for being eager to learn and handy. After finishing elementary school, he worked in a cheese factory and later in a sugar refinery in Alberta. He had a passion for mechanics and loved tinkering with engines. In his free time, he enjoyed skating and swimming. The family struggled to make ends meet, and Raymond felt the responsibility to contribute to the household income.

The photo of Corporal Raymond Aureal Seguin with his mother’s address on the back.

When Canada declared war in 1939, it did not take long for Raymond to enlist. On June 26, 1940, he signed up in Brandon, Manitoba, with the Royal Winnipeg Rifles. He summed up his motivation briefly on the enlistment form: “To hold what we have.” He received his training in Winnipeg, Shilo, and Debert. In 1941 he sailed for England, where he trained as a driver and mechanic. He proved himself to be a capable soldier and was promoted to Corporal in 1943. On June 9, 1944, three days after D-Day, he landed in Normandy with his unit. The Royal Winnipeg Rifles had already suffered heavy losses during the assault on Juno Beach on June 6. Seguin was among the reinforcements sent to fill the depleted ranks. He went on to fight in the campaigns through Normandy, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, and in the winter of 1944–1945 pushed into Germany.

Operation Veritable

In early February 1945, Operation Veritable began—the great Allied offensive launched from the Reichswald toward the Rhine. The Royal Winnipeg Rifles, part of the 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade, were tasked with opening the road to Calcar. Their advance led them past Moyland Wood, a dense forested area between Bedburg and Moyland. Here, German paratroopers and Panzergrenadiers had dug in. The terrain was harsh: waterlogged fields, shattered roads, woods where mortar shells burst in the treetops, and an enemy determined to hold its ground. The British 15th (Scottish) Division had already spent days trying to drive the Germans out but was exhausted and had suffered heavy losses. On February 15, the 3rd Canadian Division took over the sector. The next day, February 16, the Royal Winnipeg Rifles went on the attack.

The battalion’s War Diary describes the assault:

The companies assembled in the early morning and were brought forward across open ground in Kangaroos—armored carriers. Along the way, they came under heavy artillery and rocket fire, but the armor offered some protection. As the Winnipegs dismounted near their objectives and launched the attack on foot, they were met with intense fire. By about 5:00 p.m., the objectives had been secured: A, B, and D Companies occupied positions south of Moyland, while C Company was the first to break through the German lines. Around 240 German prisoners were taken. But the price was steep: “Casualties were heavy during the final assaults.” In that last assault, Corporal Raymond Seguin was killed. He was 23 years old.

The death of Raymond Aureal Seguin

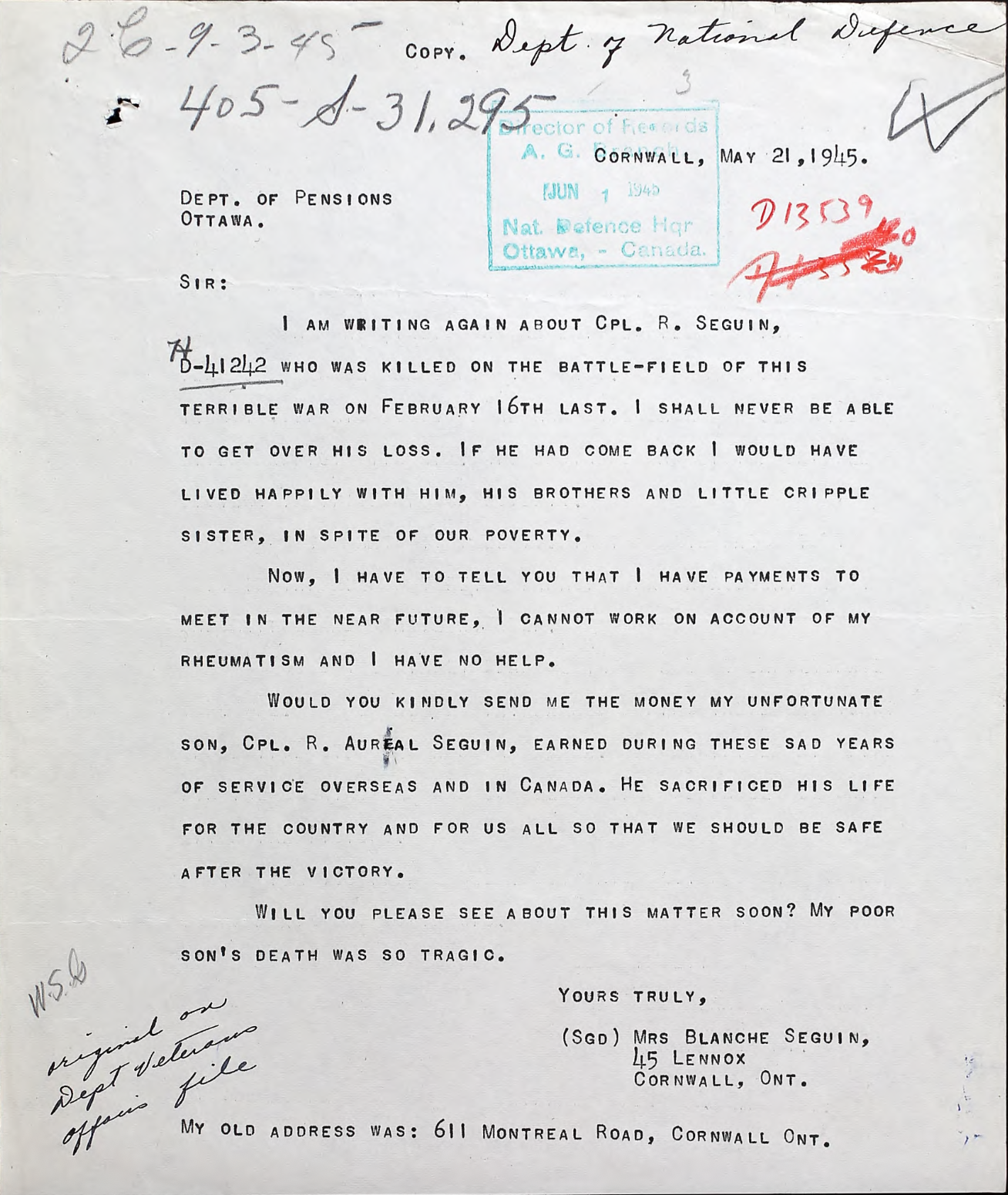

His death was reported to his mother in Cornwall by telegram. Later, she wrote in a letter to the government:

“I shall never be able to get over his loss. If he had come back, I would have lived happily with him, his brothers and little cripple sister, in spite of our poverty.”

A letter from mother Blanche Seguin to the Department of Pensions in Ottawa. © Library and Archives Canada

Her words reflect the profound emptiness his death left behind. To her, Raymond was not only a son but also the promise of support and a better future. Initially, Seguin was buried in a field grave near Calcar. Later, he was reinterred at the Groesbeek Canadian War Cemetery in the Netherlands, grave XXV.E.1. On his headstone, his mother had these words inscribed:

“Mère inconsolable te révère au ciel”

(“Heartbroken mother honors you in heaven”).

His medals—the 1939–45 Star, France and Germany Star, Defence Medal, Canadian Volunteer Service Medal with clasp, and the War Medal—were posthumously awarded to his family. The photo I found through Marktplaats was most likely taken in England. On the back, Raymond had carefully written down his details and his mother’s address. Perhaps it was meant to be sent to her, as a sign that he was doing well. But the photo was never mailed. Instead, it remained behind somewhere in Europe and resurfaced decades later in a Dutch living room. From now on, this portrait tells more than just the image of a young soldier. It is a tangible reminder of a life abruptly ended in the woods of Moyland—one of the bloodiest battles fought by the Canadian 3rd Division. The battle for Moyland Wood dragged on for another five days and cost the 7th Brigade a total of 485 casualties, 183 of them from the Royal Winnipeg Rifles. Only on February 21 were the woods fully cleared and the road to Calcar finally opened. For the Canadians, it was “the worst experience they had endured since the campaign began.” For the Seguin family, it meant the loss of a son and brother—a wound that never healed.

Canadian soldiers of the Regina Rifle Regiment preparing to attack Moyland Wood near Calcar on February 16, 1945. © Library and Archives Canada

Sources:

- War Diary, Royal Winnipeg Rifles, February 1945 (Library and Archives Canada)

- Canadian Army Official Histories – C.P. Stacey, The Victory Campaign: The Operations in North-West Europe 1944–1945

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) – Grave information of Corporal Raymond Aureal Seguin, Groesbeek Canadian War Cemetery

- Library and Archives Canada, Personnel Records of the Second World War – Raymond Aureal Seguin

- Veterans Affairs Canada – Canadian Virtual War Memorial: Raymond Aureal Seguin

- Terry Copp, Cinderella Army: The Canadians in Northwest Europe, 1944–1945

- Hugh A. Halliday, articles on Operation Veritable and Canadian participation in Moyland Wood battles