A German dagger from the Provincial Government Building in Groningen

This post is also available in:

Nederlands

Nederlands

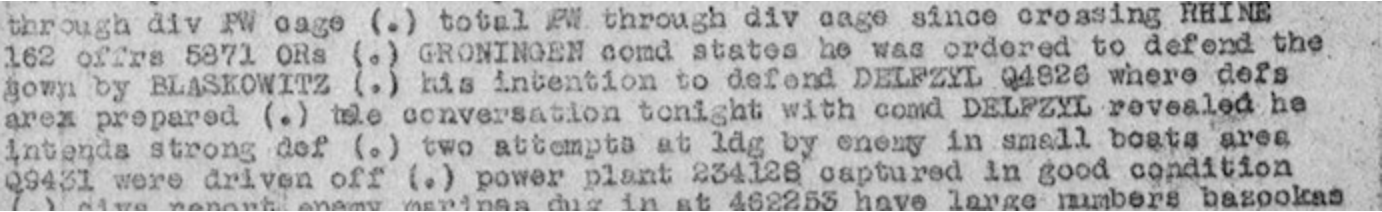

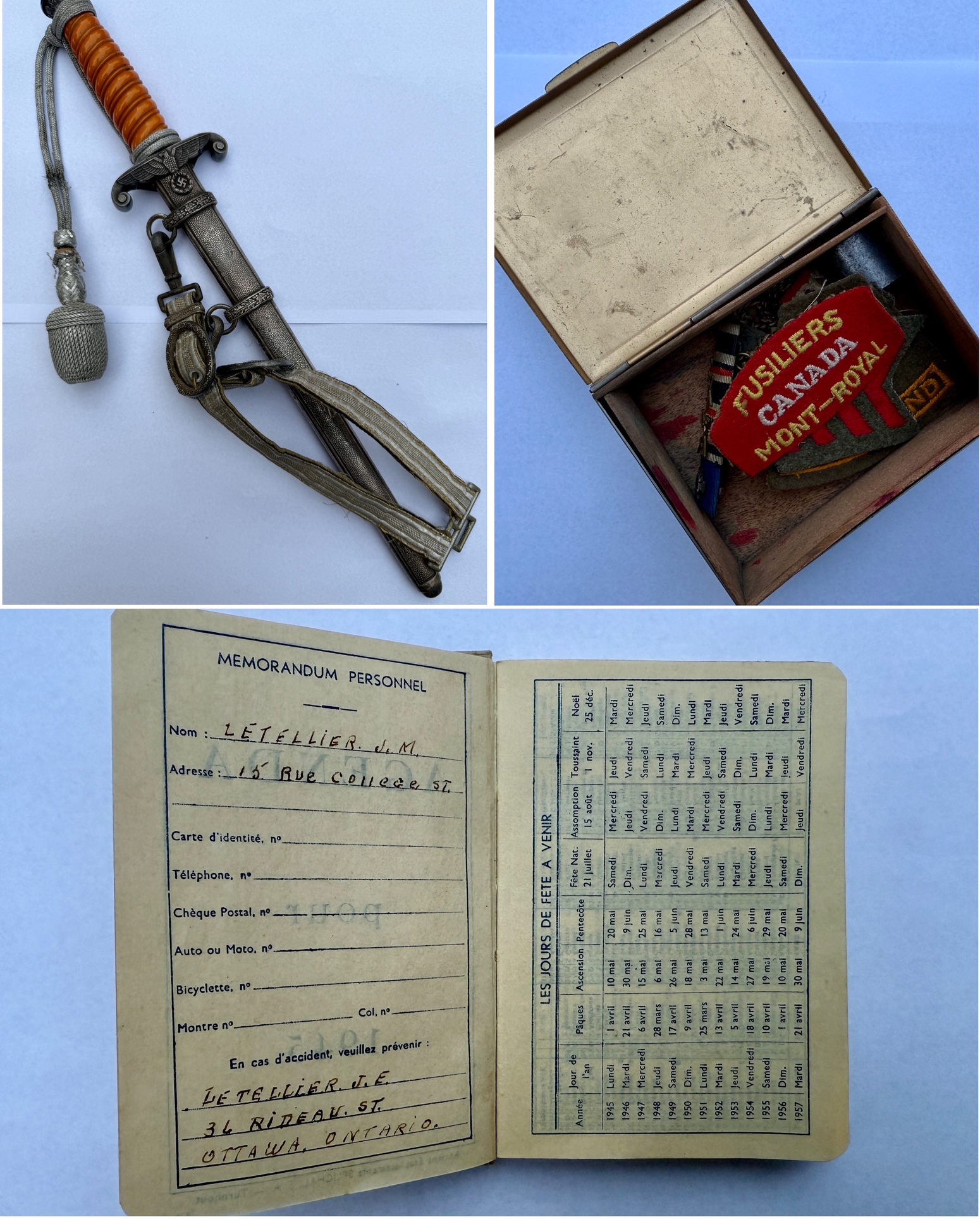

Recently, Joël Stoppels acquired a Wehrmacht officer’s dagger that was captured in April 1945 by the Canadian soldier J.M. Letellier from Ottawa at the Provincial Government Building in Groningen. This dagger, together with his regimental emblem and 1945 diary, forms the key to the story of the surrender of the German Kampfkommandant in Groningen.

In April 1945, Groningen had become a fortress city. After months of retreat, the German troops under the command of Kampfkommandant Oberst Gottfried Engelbrecht Miczek wanted to hold the city at all costs. General Johannes Blaskowitz, commander of Heeresgruppe H, had ordered the city to be defended for as long as possible in order to keep the escape route to Delfzijl open.

The attack on the city of Groningen

On the Canadian side, the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division stood ready. Under the command of Major-General Albert Bruce Matthews, the Canadians advanced from the province of Drenthe. The battle began on Friday, 13 April 1945. Tanks of the Fort Garry Horse Regiment and infantrymen of the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry (RHLI) reached the southern edge of the city. The Germans—a mix of Wehrmacht, Kriegsmarine, Luftwaffe, Dutch and Belgian SS, Hitler Youth, and railway personnel—numbered around 7,000 men. Their resources were limited: Panzerfausts, hand grenades, and a few 20 mm FLAK guns. The advance came to a halt on the Paterswoldseweg. Sergeant Walter Chaulk’s tank was hit by a Panzerfaust. Trooper Fred Butterworth was killed on the spot, the first Canadian fatality before the city. Around the Stadspark the fighting flared up; Canadian troops broke through at the Park Bridge and the Central Station, while others advanced towards the city centre via the Rabenhauptstraat and along the Hereweg.

A Canadian intelligence report reveals that during his interrogation after the battle for Groningen, the German Kampfkommandant Miczek stated that he had received orders from General Blaskowitz to defend the city for as long as possible, in order to allow the German positions around Delfzijl to be prepared. © Library and Archives Canada (LAC)

The battle for the city centre

In the days that followed, the city centre of Groningen became the scene of fierce fighting. The narrow streets, canals, and bridges rendered tanks almost useless. Fighting took place house to house, room to room. On 14 and 15 April 1945, the battle concentrated around the Grote Markt. The Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal (FMR) advanced via the Oosterstraat and took up positions on the southern side of the square. The South Saskatchewan Regiment reached the Vismarkt via the Munnekeholm. German troops had set up machine guns in the Amsterdamse Bank, the Provincial Government Building, and the Hoofdwacht. From these positions, they swept the Grote Markt with crossfire.

Eerie scenes unfolded on the north side of the Grote Markt, where the two historic façades of the Janssen clothing store were ablaze. © Anefo Photo Collection

Inferno on the Grote Markt

By the evening of Sunday, 15 April 1945, the Canadians controlled the southern side of the Grote Markt. From the Herestraat, Gelkingestraat, and Oosterstraat, tanks of the Fort Garry Horse fired on German positions across the square. Around 8:30 p.m., an ultimatum was issued over a loudspeaker: the Germans were given thirty minutes to surrender. No reply came. When the Canadians opened fire with all their weapons at nine o’clock, the Grote Markt turned into hell. The entire northern side went up in flames. German SS troops deliberately set buildings ablaze, including the Bijenkorf department store, the student society building Vindicat, and the notorious Scholtenshuis, headquarters of the Sicherheitsdienst.

In that building, hundreds of Dutch people had been tortured during the war; now it went up in flames as a symbol of the end of the occupation. Smoke, explosions, and collapsing façades dominated the scene. In the Oude Ebbingestraat, twenty shops were lost. Eyewitnesses reported that SS men in civilian clothes moved among the population, setting fires and firing from ambushes. One of them was caught and shot on the spot by the Canadians without hesitation. Despite everything, civilians, firefighters, and aid workers continued to move through the fighting. The Groningen fire brigade, under heavy fire, kept the Goudkantoor soaked and thus prevented the loss of this national monument.

The State Archives

After the Canadian ultimatum to the defenders of the Grote Markt, the remaining German troops withdrew during the night of 15 to 16 April 1945 to the Provincial Government Building and the adjoining State Archives. There, the German Kampfkommandant, Oberst Miczek, established his final headquarters. Around one hundred to one hundred and twenty men, exhausted and with no prospect of reinforcements, entrenched themselves in and around the building. The civil servant Egbert Werkman of the State Archives had initially been in the Provincial Government Building, but briefly returned to fetch some lights. To his surprise, he found German soldiers everywhere, nestled among the archive cabinets. Their mood was bleak; many had already stored away their weapons or hidden ammunition behind files and books. When the civil servant asked whether the fighting would last much longer, a German non-commissioned officer replied: “Es dauert überhaupt nicht lange mehr, wir sind eingeschloszen.” (“It won’t last much longer, we are surrounded.”) Meanwhile, the Canadians shelled the area around the State Archives with Sherman tanks of the Fort Garry Horse, while infantrymen of Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal cleared the last German positions on Sint Jansstraat and Schoolstraat. Inside the archive, resignation prevailed. Miczek sat with his head in his hands, while his staff members waited in silence for what was to come. In the basement, twenty German soldiers had thrown their rifles into a heap.

While the north side of the Grote Markt lay in ruins, the Martinitoren miraculously remained unharmed. © Anefo Photo Collection

The Surrender to Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Dextraze

When the fighting in the city centre subsided on the morning of Monday, 16 April 1945, Groningen lay largely in ruins. The last German troops from the Grote Markt had withdrawn into the State Archives on Sint Jansstraat — referred to by the Canadians as “the monastery” because of its massive walls and courtyard. That morning, Canadian Lance Corporal Arthur Duguay of the Fusiliers Mont-Royal Regiment was fatally hit at the Oosterstraat–Grote Markt intersection, presumably by fire coming from the vicinity of the Provincial Government Building. Lieutenant Colonel Jacques Alfred (“Jimmy”) Dextraze from Montreal reacted furiously and ordered mortars to be made ready in the Oosterstraat.

Around noon, a German envoy appeared at the headquarters of Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal in a house near the Carolieweg, which was also under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Dextraze. He declared that the German Kampfkommandant wished to negotiate. Dextraze, then 25 years old and only five years earlier still an ordinary soldier in the same regiment, did not hesitate: he would go himself. He climbed into a Bren Carrier, driven by Canadian Gabby Morly from Montreal. Beside him sat Private R.A. Dumaine from Western Canada and the Dutch sergeant-interpreter Willem Theodorus van Workum. They drove towards the State Archives, where the German Kampfkommandant had entrenched himself. “I am not ashamed to say that I was afraid,” Dextraze later recalled. “I entered the building with my hands in my pockets, to impress the Germans. There were about a hundred officers and men there. I went up the stairs and my legs were shaking.”

At the top of the stairs stood the German Kampfkommandant, Oberst Miczek, a German officer of about forty, neatly uniformed. Dextraze greeted him properly, raising his hand to his helmet in a military salute. Oberst Miczek returned the gesture, formal and composed. “I lit a cigarette,” Dextraze recalled, “but I didn’t offer him one.” The silence between the two men was heavy. Miczek understood why the Canadian had come. When Dextraze asked him if he was prepared to surrender, he replied curtly: “Nein. Ich will nur verhandeln.” (“No. I only want to negotiate.”)

The interpreter, Sergeant Van Workum — who spoke fluent German — took over the conversation and addressed the commander: “Herr Oberst, bitte kommen Sie heraus. Sie haben keine Chance mehr. Sie sind eingeschlossen. Es hat keinen Sinn, weiter zu weigern.” Dextraze began to grow impatient; it was taking too long, and he voiced his frustration to Van Workum. The latter then adopted his most authoritative tone and made one final appeal to Miczek’s reason: “Kommen Sie heraus, seien Sie vernünftig.” Dextraze added sternly:

“My battalion has orders to storm this building if I am not back within fifteen minutes. I may be killed in the attempt, but you will surely die. Think carefully about that.”

By saying that he underscored his words by putting a time limit on the choice — fifteen minutes to choose between honour and ruin. Miczek appeared shocked. He could not believe that other German officers had already surrendered. Dextraze assured him that four German lieutenant-colonels had been taken prisoner that same morning. When Miczek was still not convinced, Dextraze offered to take him to the Canadian headquarters so he could see for himself. A few minutes later they left the State Archives together. Outside, Canadian carriers and armed soldiers were deployed. When Miczek realised that Dextraze was telling the truth — that the city was surrounded and the fight was lost — he nodded slowly. Before he fully surrendered he made one last request: “Ich will, dass die Bevölkerung nicht serum staat,” he asked. (The German phrase in the original appears to be garbled; it likely expresses a plea concerning the civilian population — e.g. that the population should not be harmed or should remain unharmed.) Dextraze simply agreed to this. Shortly after one o’clock in the afternoon, in the State Archives at the Martinikerkhof, Kampfkommandant Miczek capitulated. The German soldiers threw their weapons into a pile and then formed up outside in rows of three. In total 132 German soldiers were taken prisoner.

On 16 April 1945, the German column, led by Kampfkommandant Miczek, marched through the Oosterstraat on their way to captivity.

© Oorlogs- en Verzetscentrum Groningen

As the Germans prepared to march off, Dextraze turned to Miczek with the request to hand over his pistol. “His face darkened and turned pale as he handed it to me,” Dextraze later recalled. Miczek even thanked him for the proper manner in which the negotiations had been conducted and extended his hand. Dextraze:

“I had only done my duty, but he should not forget that he was a German and I a Canadian — and that for that reason I could not shake his hand.”

With those words, the battle for Groningen came to an end. For his leadership during the liberation, Lieutenant Colonel Dextraze was awarded a bar to his Distinguished Service Order (DSO). He would later rise to become Chief of the Defence Staff of the Canadian Armed Forces. The Dutch interpreter, Sergeant Willem Theodorus van Workum, was decorated with the Military Medal for his courageous role in the negotiations.

The end of the battle

The capitulation did not mean that the danger in the city of Groningen was over. SS men in civilian clothes remained active for several days. The Canadian army command issued orders that these snipers were to be shot on sight without mercy if confronted. When silence finally fell, Groningen counted its losses. Forty-three Canadian soldiers had been killed and 166 wounded. On the German side, about 130 were killed. Among the civilian population, 110 lives were lost, and 207 buildings were destroyed or severely damaged. On 19 April 1945, Canadian Major-General Matthews visited the city hall, where Mayor Pieter Cort van der Linden appointed him an honorary citizen of the city. Matthews, in turn, presented the Canadian garrison flag to the city. The Canadians of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division then moved on to Oldenburg in Germany. Groningen was free.

The captured Wehrmacht officer’s dagger, accompanied by a small box containing Canadian insignia – including the regimental uniform title of the Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal – and the 1945 pocket diary of Canadian veteran J.M. Letellier. © Collection Joël Stoppels

The Wehrmacht officer’s dagger from the Provincial Government Building

Among the men who moved through the city centre during these days was Canadian veteran J.M. Letellier from Ottawa, Ontario, of the regiment Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal. During the liberation of Groningen on 16 April 1945, he entered the Provincial Government Building, where German officers had only recently been stationed. Among the abandoned uniforms and maps, Letellier found a Wehrmacht officer’s dagger. He took the weapon as a war trophy. Joël Stoppels have the privilege of adding this object to his collection. Together with Letellier’s diary and regimental emblem, it now forms part of the story of the surrender in the State Archives of Groningen.

The captured Wehrmacht officer’s dagger from the Provincial Government Building in Groningen. © Collection Joël Stoppels

Sources:

- War Diary Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, April 1945. Library and Archives Canada (LAC)

- De bevrijding van Groningen, W. K. J. J. by Ommen Kloeke. 1945.

- “Een archief in de frontlijn” Een ooggetuigenverslag van de gebeurtenissen in en rond het Provinciehuis van de stad Groningen tijdens de bevrijding in april 1945. Nederlands Archievenblad. 1945.

- Endkampf om Groningen april 1945 by Sipke de Wind.