A deadly New Year’s Day in 1945

This post is also available in:

Nederlands

Nederlands

After the Battle of the Scheldt, the II Canadian Corps took over the Nijmegen salient from the 30th British Corps on 9 November 1944. Their forward positions stretched from Cuijk, opposite the Reichswald, across the ‘Arnhemse island’ to Maren. They dug in along the Maas and the arch of Nijmegen. On this static front, the Canadian soldiers had to withstand artillery fire, dangerous patrols, rain, wind and bitter cold.

Patrols in the winter of 1944/1945

Throughout the late autumn and early winter of 1944/1945, Canadian units at the front maintained a program of “aggressive patrols” to collect as much information as possible on the nature and condition of German defenses and the strength of troops. Under the cover of darkness, combat patrols pushed forward as far as possible to “locate and ascertain the strength of the enemy’s main line of defence”. There were four types of patrols. Reconnaissance patrols were sent out to gather information without fighting for it. The combat patrols were aimed at capturing German soldiers, destroying enemy positions or gathering information. These patrols normally consisted of ten or twelve men and they were willing to fight to accomplish their mission. Thirdly, there were contact patrols, which established communication with the flanking units. Finally there were ‘standing patrols’, these were no more than one platoon in strength and protected the main defense positions and gave early warning of German counter-attacks. Such patrols were prepared to fight, but not to hold out at all costs.

1 January 1945

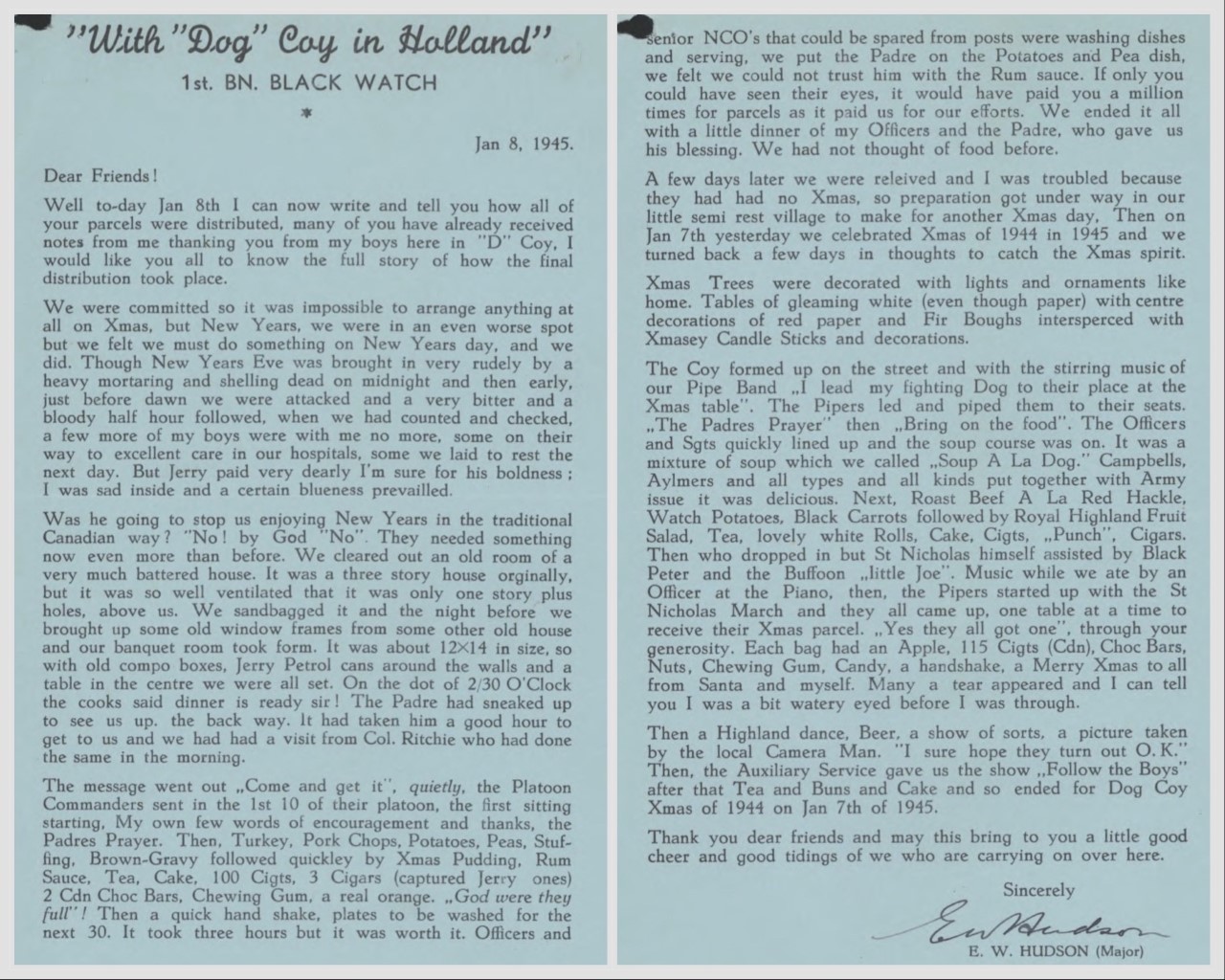

The Germans start the new year of 1945 with a massive artillery bombardment on the Canadian positions around Mook. The year literally started with a huge bang, most guns were aimed in the air and a lot of tracer ammunition was fired. Despite this beautiful display, the D Company of the Black Watch of Canada could not appreciate it. Most of the artillery and mortar shells hit their area. Fortunately, the shelling only lasted a few minutes and there were no casualties. Because it was a clear night with a full moon, the deployment of a combat patrol was initially abandoned.

Besides bright moonlight, there was a thick layer of ice and frost on the field to be crossed. But despite the unfavorable conditions for a patrol, the Black Watch received an order from headquarters for a combat patrol. A prisoner of war would have to be made for any information about the strength of the enemy.

The patrol on its way

Lieutenant R.F. Davey set out with two NCO’s and 9 soldiers to capture a German soldier. During the first reconnaissance they arrived at a ruin of a house on the Katerbosseweg in Middelaar. After firing a PIAT anti-tank grenade into the house, they went inside. One of the Germans ran away through the corner of the house, no Germans were found in the house itself. The patrol then continued towards a house on the Elzensteeg, but nothing was found here either. Two German machine guns fired convulsively from the dike around the Witteweg, but despite the fact that the patrol fired a lot of ammunition and made a lot of noise, there was remarkably little action from the German lines. The patrol returned without a POW at 03:50 PM.

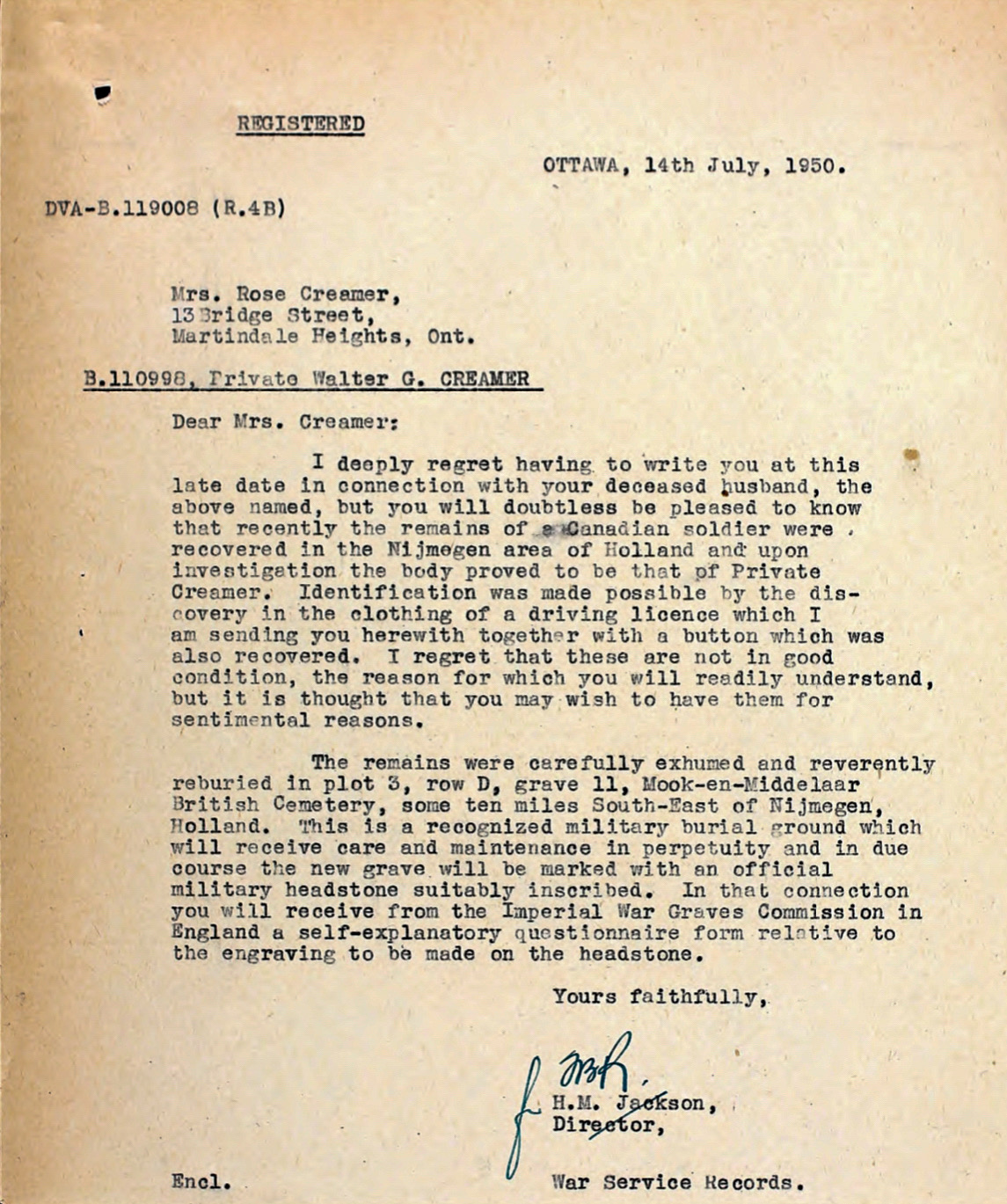

A letter to the wife of Private Creamer about the discovery of his body in Nijmegen. Library and Archives Canada.

A deadly German counter-attack

At around 07:15 AM, a massive shelling suddenly ensued on the positions of the D Company. It was assumed that the Germans were engaged in a counter-attack. One isolated outpost had yet to be connected to the rest of the platoon by a communications trench and was within 50 yards of the German positions. Mortars and automatic weapons were used by the Germans to ensure that no further reinforcements could be sent forward by the Canadians. To increase the confusion, the Germans also used bazookas and Panzerfausts. This attack overran the four-man outpost, killing Private Kenneth David Grainger, John Emerson Dauncey, and Lance Corporal Henon James Connor.

Private Walter George Creamer was a Bren Gunner in the outpost and was probably wounded by a hand grenade, he remained missing until July 14, 1950. His remains were later found in Nijmegen. After the attack, the Germans withdrew in a controlled manner. According to The Black Watch’s War Diary, it is not clear how many Germans were killed in this attack, presumably they took their dead back to their own lines. After 17 days on the front line, it was the first German counter-attack of the new year against the positions of the Black Watch of Canada around Mook.

New Year’s Eve party on January 7 for The Black Watch of Canada’s D Company

Sources:

- War Diary, Black Watch of Canada. January 1945. Library and Archives Canada.