D-Day in Normandy 1944 | Then and Now

This post is also available in:

Nederlands

Nederlands

No other World War II battle has made more of an impact than the landing of 125,000 Allied soldiers on the beaches of Normandy on June 6, 1944, known as D-Day. This impressive then & now photo series takes you from the invasion on June 6, 1944 to the battle of the Falaise Pocket.

The Normandy Invasion

Four years after the crushing defeat of France, Belgium and the Netherlands in the spring of 1940, the Western Allies launched Operation Overlord. The aim was to establish a bridgehead in Western Europe from which to defeat Nazi Germany on the Eastern Front with the help of the Soviet army. Normandy was chosen for its proximity to the British coast. This enabled the Allied Air Force to effectively support the landing troops at the start of the attack (Operation Neptune). Above all, the German defenses along this part of the coast were less strong than further north. The German High Command expected the Allied landings where the Channel was narrowest.

A fleet of more than 6,900 ships was needed to put the assault troops of more than 156,000 soldiers on five beaches. The landing beaches were codenamed Utah and Omaha (US), Gold (British), Juno (Canadian) and Sword (British) from west to east. About 24,000 airborne troops were deployed to capture strategic points to prevent the Germans from attacking the flanks of the troops landing on the coast.

Despite the bad weather and fierce German resistance, the operations were successful. On the evening of June 6, 1944, the Allies had a firm foothold on all five beaches. The German defense did not know how to react. D-Day was primarily a British-American effort. British, American and Canadian troops formed the main body, but in total 17 allied countries participated in the air, at sea and on land. The landings of June 6, 1944 made history under the legendary name D-Day.

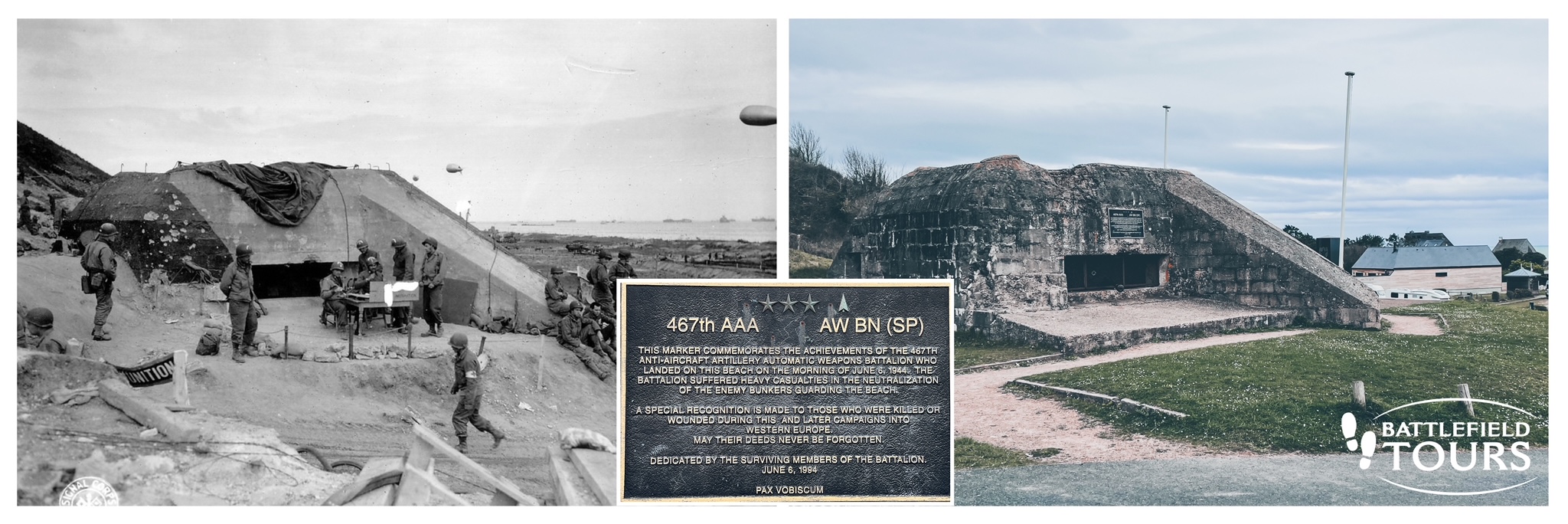

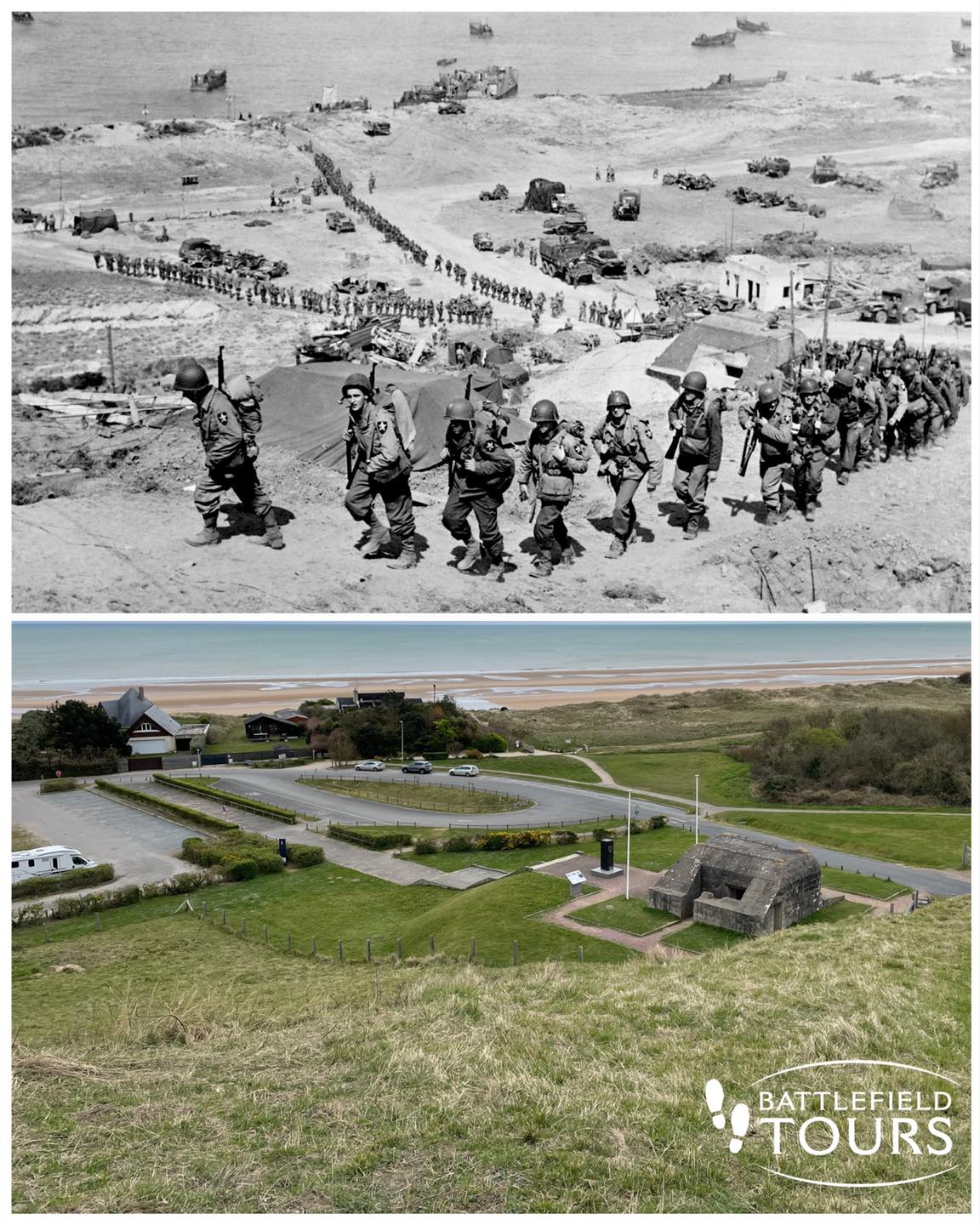

This photo shows troops of the US 2nd Infantry Division going up the bluff via the E-1 draw on D+1, June 7, 1944. They are going past the German WN-65 casemate that defended the route up the Ruquet Valley to Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer. E-1 was cleared fairly early and became the main exit from Omaha Beach on D-Day, largely due to the efforts of the 37th and 149th Engineer Combat Battalions. The 37th suffered 24 men killed including its commander.

Two of its bulldozer operators, Privates Vinton W. Dove and William J. Shoemaker of Company C, were both awarded Distinguished Service Crosses (DSC) for clearing the road through the shingle and filling in the anti-tank ditch while under intense enemy fire, the German gunners having singled out the bulldozers as prime targets. Company C’s 1st Lieutenant Robert P. Ross won the third DSC awarded to the 37th on D-Day for helping Company B, 16th Infantry, to silence WN 64 on the Hillside overlooking E-1 in a battle in which 40 Germans were killed. After its capture, the Engineers took over the 50mm casemate for use as their command post.

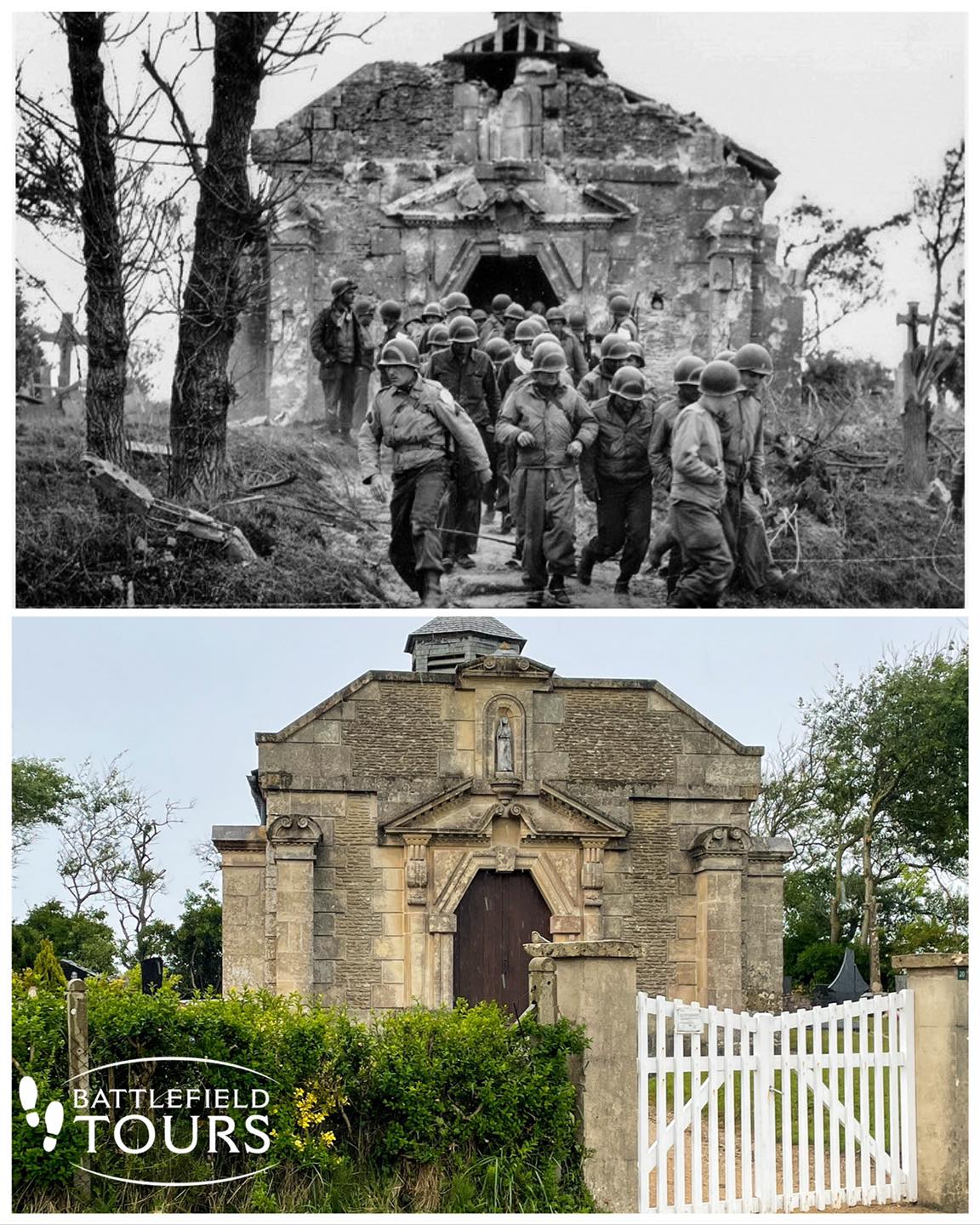

To the northwest of Utah Beach, stood the chapel of La Madelèine (W4). This photo was taken a few days after D-Day and shows sappers of the 1st ESB (Engineers Special Brigade) leaving the chapel after a service. The unit’s mark, a white arc, can be seen painted on their helmets. This fine chapel, typical of the first half of the 17th century, was restored after bomb damage and continues to be a landmark near Utah Beach.

The photos of the paratroopers of the 82nd Airborne Division in Sainte-Mère-Église are particularly famous. They have often been published and have contributed towards the huge celebrity of this little French town. “The Longest Day”, first the Cornelis Ryan book then the movie based on it, turned this Cotentin village into one of those places found in history books.

This famous photo shows paratroopers from the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment in Sainte-Mère-Église. The paratroopers rounded up horses and horse drawn carts, of which there were plenty in this sector of Normandy, mostly taken from the Germans, most of whose static units in position in the Cotentin peninsula were horsedrawn. After Sainte-Mère-Église was taken, these patrols would appear to have taken place on 7 June 1944. The place has remained intact, apart from changes in the signposting.

In the Main Street of Sainte-Mère-Eglise, facing north towards Fauville, an 88 shell has ripped open the corner of a house. Medics of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division load up an American GMC truck with wounded Americans and civilians. The men have their backs to the Town Hall, on the left where the Germans had set up the Kanton Kommandantur. On the right, wearing a dark jacket and a French helmet is a civilian medical orderly.

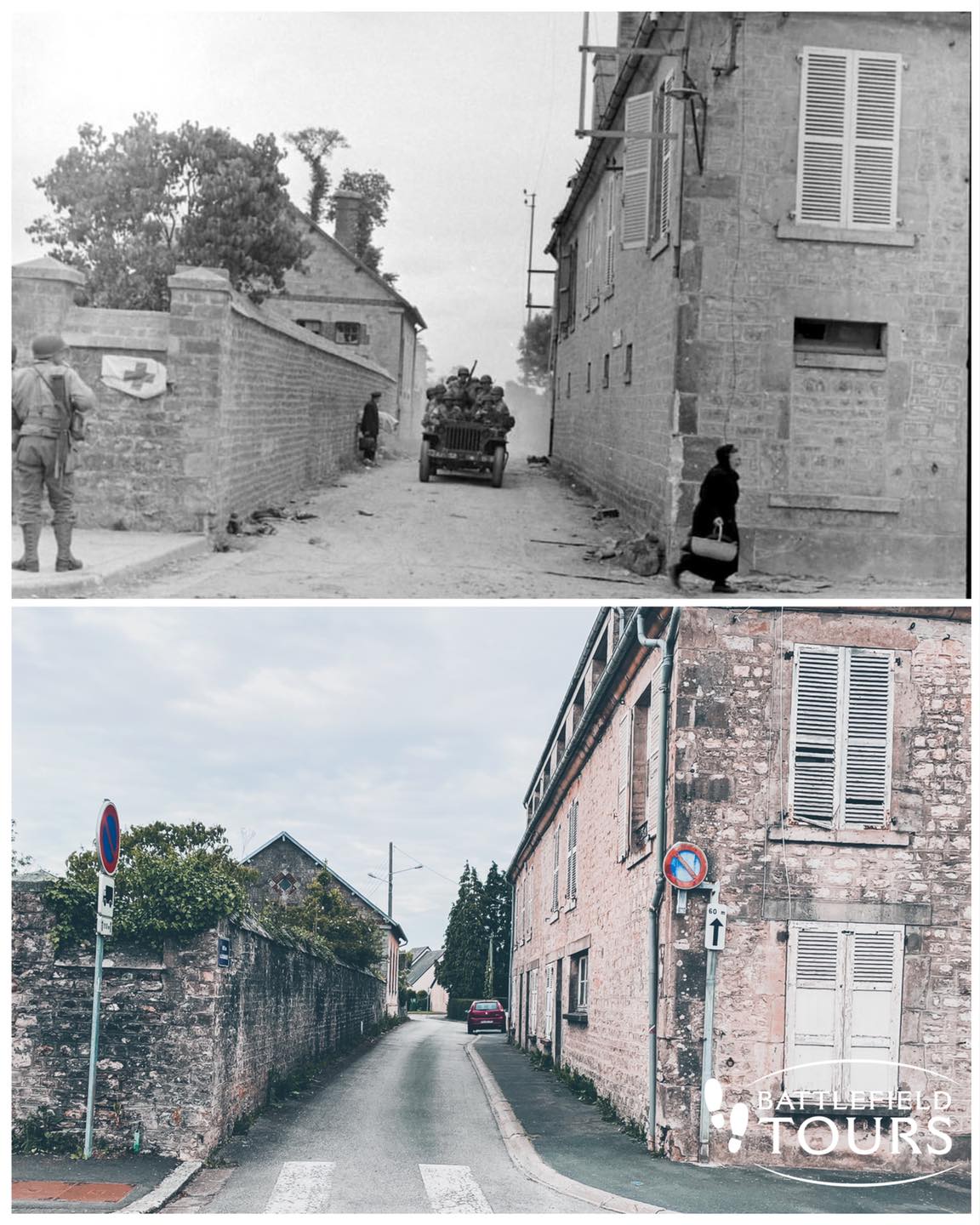

On the morning of June 7, 1944 (D-Day + 1), the 4th US Infantry Division from Utah beach had joined the paratroopers of the 82nd Airborne Division at Sainte-Mère-Eglise. This photo shows a fully loaded jeep with American soldiers. The 505th Regimental Aid Station #2 was set up in the former Hospice on the left. At the end of June 6, 1944, there were already 120 wounded Americans in this former Hospice. After 78 years, the situation on the Rue du Cap de Laine has hardly changed.

Paratroopers of the 82nd Airborne Division are resting on the foot of the Église Saint-Marcouf. For a long time this reportage used to be dated June 8, 1944. However identifications have dated it to D-Day, which is confirmed by the fact that the men in this photo still have their faces blackened with the greasepaint they put on before leaving on the evening of 5 June. On the present day photo, notice how the steps leading to the cemetery have been modified.

On 7 June 1944, a US Navy photographer pictured the square of St. Marie-du-Mont with the war memorial on the right. One of a number of plaques, set up in the French town to commemorate the events of 1944, has now been mounted on the pump.

St. Marie-du-Mont lies on the eastern edge of DZ ‘C’ in the heart of the 101st Airborne divisions operational area. With its peculiar domed-steeple church in the central market square, it bears a similar meaning for the 101st as St. Mère-Église does to the 82nd.

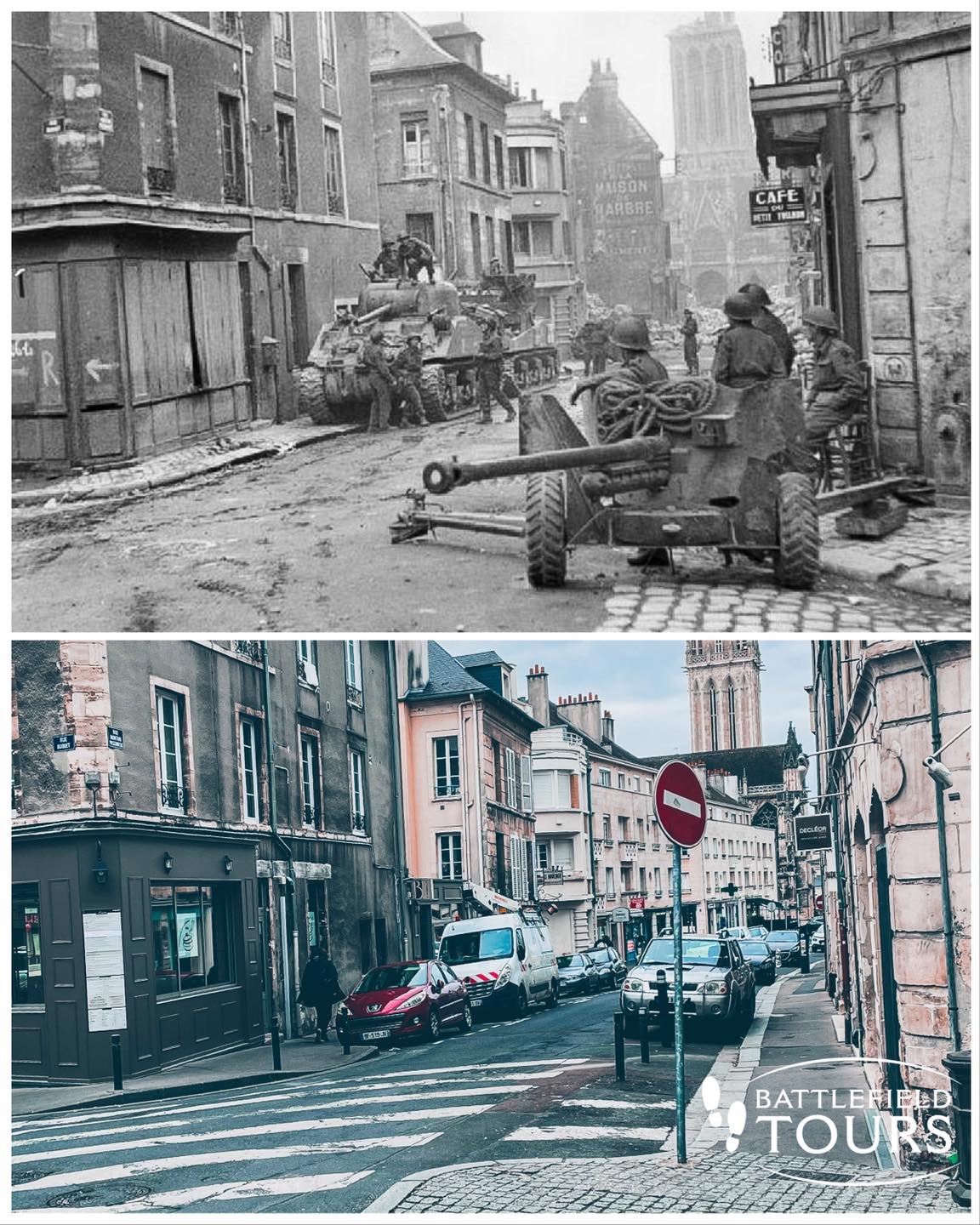

Then and now photo of British Sherman tanks and soldiers of the 1 Kings Own Scottish Borderers (KOSB), 9th Brigade, 3rd Infantry Division in the streets of Caen on July 10, 1944. Caen, the ancient capital of Normandy, was a vital road and rail junction that the Allies needed to capture before they could advance south through the excellent tank country of the Falaise Plain. Because of its strategic significance, the Allies had to fight doggedly to overcome a well prepared and resolute German defense. Instead of one day, it took the Allies six weeks to capture the city. It was a Pyrrhic victory, with a devastating toll. About 24,000 Anglo-Canadian soldiers were casualties. 70% of the town was destroyed and it lost 3,000 of its inhabitants.

Photo source: Ⓒ IWM B 6924

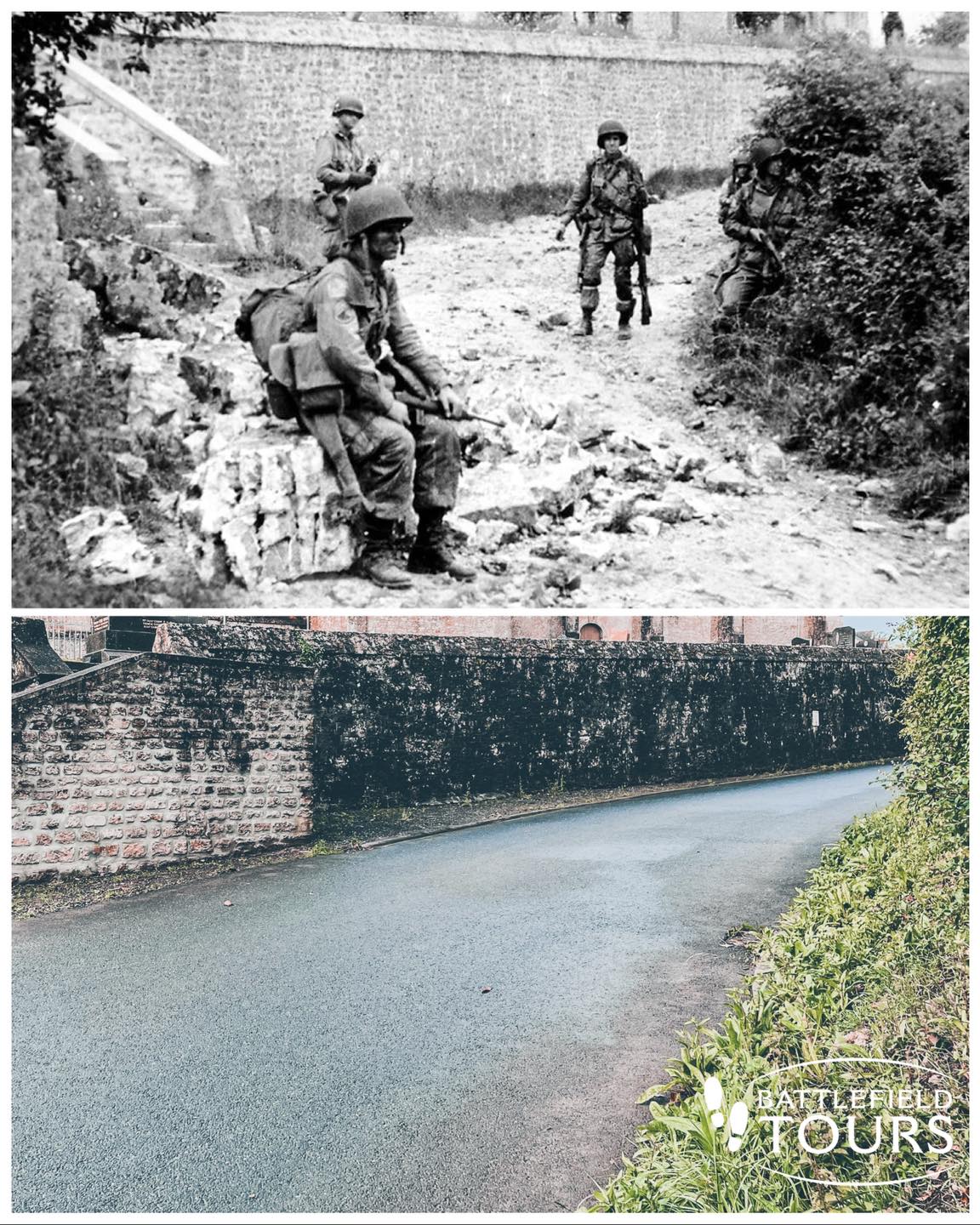

This amazing then and now photo shows Scottish soldiers of the 1 Kings Own Scottish Borderers (KOSB), 9th Brigade, 3rd Infantry Division at the Rue des Chanoines in Caen on July 9, 1944. On D-Day, Caen was an important Allied objective as it was an essential road hub, strategically astride the Orne River and Caen Canal. The Germans defended this area with all their power and the civilian population of Caen would pay a terrible price during this heavy battle. Only in the morning of 9 July 1944, British troops from the east and north, and Canadians from the west were able to make their way gingerly into what was left of the ruined city.

A then and now photo of the scene of destruction in the village of Cagny in Normandy on 19 July 1944. This picture was taken during operation Goodwood, this offensive took place between 18th and 20th July 1944. The objective of this operation was a limited attack to the south, to capture the rest of Caen and the Bourguébus ridge beyond.

At 09:15, the tanks of the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment (3RTR) crossed the armoured corridor safely, but were stopped by the German defenses at Grentheville. At 10:15, the first two squadrons of the Fife and Forfar Yeomanry (2FFY) arrived at the Caen-Vimont railway without much German opposition. Meanwhile, the German Lieutenant-Colonel Hans von Luck, commanding the combat group at the center of the German feature, reorganized the defense. In Cagny, he turned the FLAK 88mm anti-aircraft guns on the tanks of the 3rd Squadron of the Fife and Forfar Yeomanry which passed in front of the German positions. The advance was stopped when 15 out of the 19 British tanks were destroyed instantly.

The situation was chaotic. German Mark IV tanks of the Panzer Regiment 22 counter-attacked the tanks of the 23rd Hussars that followed. All the Mark IV tanks except one were knocked out. At 10:30, the 8th Rifle Brigade took Le Mesnil-Frementel, taking 134 German prisoners. Around noon, Panzeroffizier Richard von Rosen, commanding the 3rd company of the fearsome German Tiger tanks of the Schwere Panzer-Abteilung 503 attempted an attack from the south on Manneville. Two of his tanks where hit by German shells from the direction of Cagny and cought fire. Eventually the Guards took over from the 11th Armored Division.

The tanks of the 2nd Guards assisted by infantry and assault guns inflicted furthur losses on the Germans who retreated. Cagny was captured in the late afternoon.

The Dives Valley between Falaise and Chambois, north of the road from Argentan to Paris, was the scene of fierce fighting from 19 to 21th August 1944. 100.000 Germans and 150.000 Allied soldiers clashed over a few square kilometres. As the Allies drew closer, German troops evacuated the sector by forced march. As of 15th August, the “cauldron” was subjected to a deluge of fire by Allied artillery and bombardments and counterattacks by the Germans, eager to keep their escape route clear. The “corridor of death”, an escape route branching into numerous paths, was closing up day by day.

On 19th August, Polish soldiers from the 1st Armoured Division took possession of Mont-Ormel in Coudehand. On the same day, joining up with the Americans who had come from the south, they closed the circle in Chambois.

The encircled German army counter-attacked to break through in the Montormel sector. The Polish forces, caught in a vice by a German attack from the rear, put up a heroic resistance often in hand-to-hand combat. The fighting was still continuing on 21th August. At noon, Canadian and Polish forces joined up in Coudehand, sealing the final closure of the pocket. The encircled German troops surrendered to the Allies in Tournai-sur-Dive. After this the battle of Normandy was over. This then and now photo shows a destroyed German Panzer IV and halftrack for the crossing of the River Dives in Chambois. In the background, the church continues to watch over the bridge…

Amazing then and now photo of Canadian troops from Major David V. Currie of the South Alberta Regiment accepting the surrender of German troops at St. Lambert-sur-Dive in Normandy on 19 August 1944. This photo captures the very moment and actions that would lead to Major Currie being awarded the Victoria Cross.

During the last stages of August 1944, the allies were encircling the German armies in Normandy. The Germans were desperately attempting to escape the ‘Falaise pocket’ through the village of St. Lambert-Sur-Dive. Major D.V. Currie, officer commanding “C” Squadron of the South Alberta Regiment (SAR), 29th Canadian Reconnaissance Regiment with under command detachments from the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada, The Lincoln and Welland Regiment and A Troop of the 5th Anti-tank regiment, was charged with the closing of the Falaise gap in this area. After suffering heavy casualties during three days and nights, with no officers left except Major Currie, the gap was finally closed.

Throughout it all, Currie remained calm and firm, overcoming overwhelming odds to beat the Germans. When the counterattacks finally ended, Currie’s troops emerged victorious with 300 of the enemy killed, 500 wounded, and 2,100 taken as prisoners of war. They also destroyed seven tanks and 40 vehicles in total. For gallant leadership throughout this battle, Major Currie was awarded the Victoria Cross. This was the only Victoria Cross awarded to the Canadian Armoured Corps during World War II.

Source: Citation Major D.V. Currie

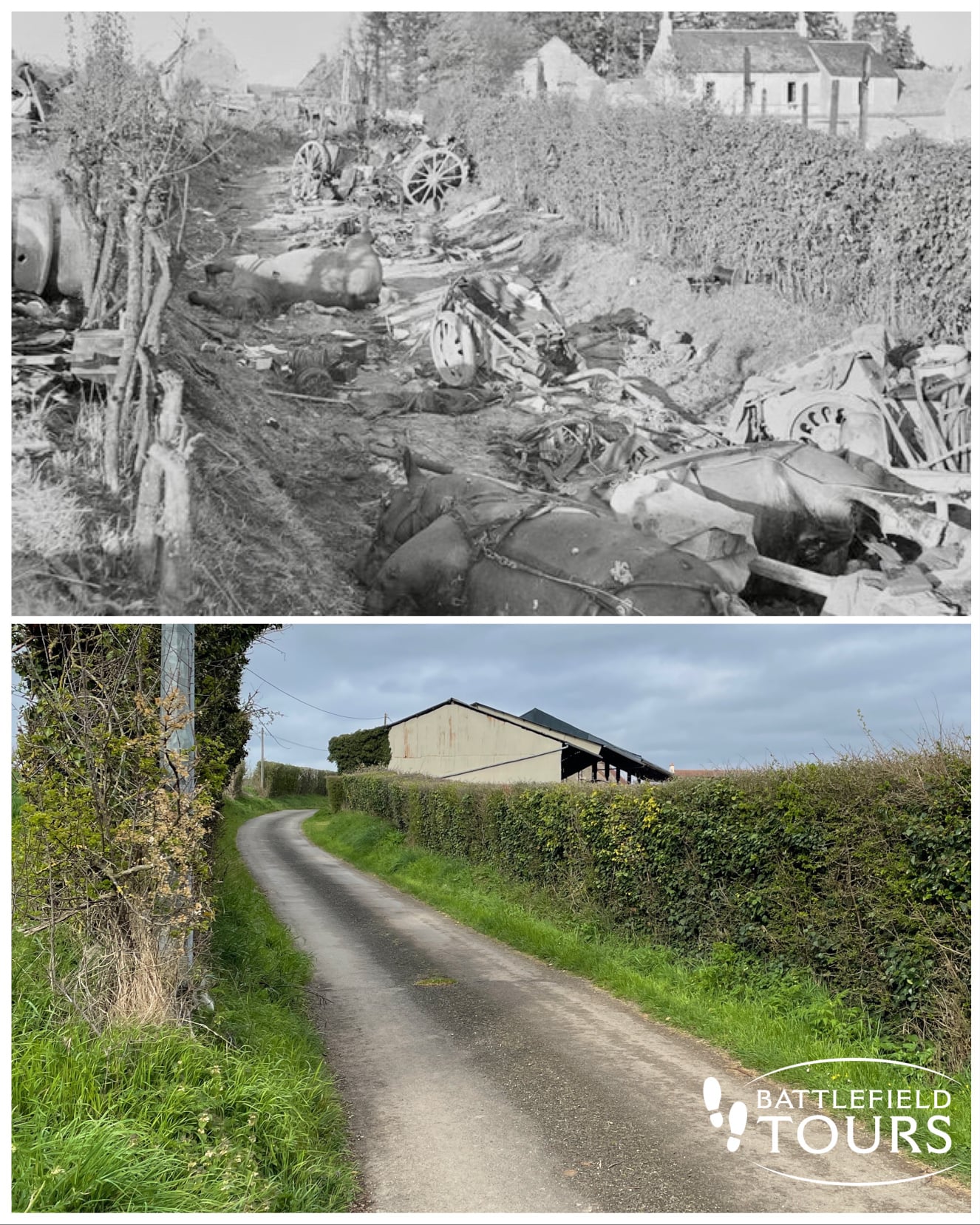

This photograph of the congested road is often used to symbolize the corridor of death in the Falaise Pocket. The same road (below), clear this time, with the farm behind the hedge in the background.

When the battle of the Falaise Pocket was over, soldiers and civilians were struck by the violence of the battle and the scenes of desolation. About 50.000 German soldiers managed to escape through gaps in the pocket. Between 5.000 and 10.000 men were killed. 40.000 to 50.000 were taken prisoner.

Sources:

- Builders and Fighters: U.S. Army Engineers in World War II by Barry W. Fowle.

- Omaha Beachhead (6 June–13 June 1944). American Forces in Action Series (2011 Digital ed.). Washington DC: Historical Division, War Department. 1945. OCLC 643549468

- Citation Victoria Cross Major David Vivian Currie

- Sainte-Mere-Eglise, Photographs of D-Day – 6 June 1944, Michel De Trez